A hand-picked selection of fine and extolled English language poetry.

Sheel Khemka of Word Soup pays tribute to some of our much loved and lauded English language poets, inspired out of little short of an out and out love affair with the genre (of poetry)

- and the oft’ visceral, bracing, irrevocable power of words.

Sometimes it’s just simple words … something in the way they were – quite simply - put together.

“There's no money in poetry,

but there's no poetry in money,

either.”

— Robert Graves

“We make out of the quarrel with others, rhetoric, but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry.”

— William Butler Yeats

In actual fact it was Romantic poetry, that is

– as in poetry from the Romantic period that took place in Europe in literature and the arts from around the late 18th to the mid-19th century -

and as distinct from romantic as in love –

that was the prima facie, overriding catalyst here.

Indeed the propelling, motivating factor for the inspired effort that it took- in the compiling together of this brisk but brimful compendium of simply loved and cherished poems and excerpts.

Mount Vesuvius in Eruption, example of a Romantic work of art

by J.M.W. Turner, 1817

Romanticism in poetry.

For when it comes to Romantic poetry (poetry of the Romantic period, that is), key is its direct appeal to - and often resonant synchronicity with - call it that soft inner substance of our sensory chords and perceptions

(of the mind, the ear, and the soul) -

through its prolific use of elaborate, high octane, highfalutin imagery and diction

- not to mention the well-noted, extended metaphor.

While it also champions vigorous, intense, truly spontaneous responses to the world that we encounter,

the focus being on an untrammelled authenticity.

Which gives rise to a unique and powerful visual experience for the reader or listener.

At the same time its ornate high art lyrical style comes oft’ draped in a melody as would

altogether and at once

render you right down to your knees,

and make your heart strings just melt;

or combust, and at no mean fahrenheit at that.

– It’s something in the exquisite quality of the words,

and their sound.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1792-1822

For example, consider below the piercing liquid crystal sound of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s skylark, in To A Skylark, where the bird ascends ever higher into the mid afternoon sky, the cadences and rhyme of the verse echoing the singing voice (of the bird) as if in real time, all framed within elaborate, extended metaphor.

It’s reminiscent of that bygone classical era – of the halcyon days, of ancient Greece, and of Homer.

So take for example when Homer in The Iliad (that his great Greek epic of circa 700 BCE, one yet to meet it’s match in possibly any language or period ever since) introduces Hector of the gleaming helmet*, what then happens is you’re led through a journey of several lines if not stanzas worth of descriptive material (all pivoted on and escalating the adventures of said gleaming helmet*), that is replete with extended metaphor - namely a series of linked and melodious, meticulously detailed comparatives in turn (and mostly nature driven comparatives, thereby bringing the high-flown subject matter of epic battle into a more relatable sphere of reference at the same time), with each one amplifying and working on – reinforcing - the other. Such that by the end one is so subsumed within this metaphor led, and hence vividly brought to life, textured world of legend, Gods and war that’s been created, that one’s quite ready to embrace for actual fact the true God-stature of Hector, the man - where the fiction becomes the reality; all nobly performed through the layered use of conceits (i.e. metaphor).

Similarly with Shelley’s skylark, and that fleeting sense of the divine:

To a Skylark

Hail to thee, blithe Spirit!

Bird thou never wert,

That from Heaven, or near it,

Pourest thy full heart

In profuse strains of unpremeditated art.

Higher still and higher

From the earth thou springest

Like a cloud of fire;

The blue deep thou wingest,

And singing still dost soar, and soaring ever singest.

In the golden lightning

Of the sunken sun,

O'er which clouds are bright'ning,

Thou dost float and run;

Like an unbodied joy whose race is just begun.

The pale purple even

Melts around thy flight;

Like a star of Heaven,

In the broad day-light

Thou art unseen, but yet I hear thy shrill delight,

Keen as are the arrows

Of that silver sphere,

Whose intense lamp narrows

In the white dawn clear

Until we hardly see, we feel that it is there.

All the earth and air

With thy voice is loud,

As, when night is bare,

From one lonely cloud

The moon rains out her beams, and Heaven is overflow'd.

What thou art we know not;

What is most like thee?

From rainbow clouds there flow not

Drops so bright to see

As from thy presence showers a rain of melody.

Like a Poet hidden

In the light of thought,

Singing hymns unbidden,

Till the world is wrought

To sympathy with hopes and fears it heeded not:

Like a high-born maiden

In a palace-tower,

Soothing her love-laden

Soul in secret hour

With music sweet as love, which overflows her bower:

Like a glow-worm golden

In a dell of dew,

Scattering unbeholden

Its aëreal hue

Among the flowers and grass, which screen it from the view:

Like a rose embower'd

In its own green leaves,

By warm winds deflower'd,

Till the scent it gives

Makes faint with too much sweet those heavy-winged thieves:

Sound of vernal showers

On the twinkling grass,

Rain-awaken'd flowers,

All that ever was

Joyous, and clear, and fresh, thy music doth surpass.

Teach us, Sprite or Bird,

What sweet thoughts are thine:

I have never heard

Praise of love or wine

That panted forth a flood of rapture so divine.

Chorus Hymeneal,

Or triumphal chant,

Match'd with thine would be all

But an empty vaunt,

A thing wherein we feel there is some hidden want.

What objects are the fountains

Of thy happy strain?

What fields, or waves, or mountains?

What shapes of sky or plain?

What love of thine own kind? what ignorance of pain?

With thy clear keen joyance

Languor cannot be:

Shadow of annoyance

Never came near thee:

Thou lovest: but ne'er knew love's sad satiety.

Waking or asleep,

Thou of death must deem

Things more true and deep

Than we mortals dream,

Or how could thy notes flow in such a crystal stream?

We look before and after,

And pine for what is not:

Our sincerest laughter

With some pain is fraught;

Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thought.

Yet if we could scorn

Hate, and pride, and fear;

If we were things born

Not to shed a tear,

I know not how thy joy we ever should come near.

Better than all measures

Of delightful sound,

Better than all treasures

That in books are found,

Thy skill to poet were, thou scorner of the ground!

Teach me half the gladness

That thy brain must know,

Such harmonious madness

From my lips would flow

The world should listen then, as I am listening now.

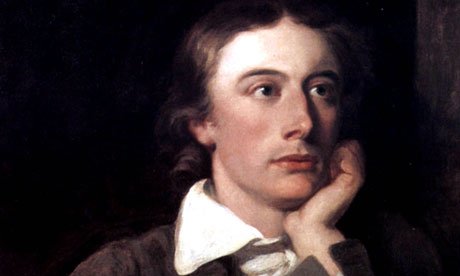

John Keats, 1795-1821

Consider then also Keats’s own plethora of layered sensualities, in his ode To Autumn (below), where he draws on nature - with lines that could cut through you like a blade, even if only for that first moment you heard. It’s like a poetic gift on another level, one which you knew you could only strive for (if of your own accord), and never quite achieve, however dextrous or agile you thought you might be in the poetry department.

Subliminally aware at the same time that this kind of verbal divination is also no doubt a product of its time, scion of that singular epoch in our given linguistic past.

To Autumn, by John Keats

To Autumn

BY JOHN KEATS

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss'd cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For summer has o'er-brimm'd their clammy cells.

Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reap'd furrow sound asleep,

Drows'd with the fume of poppies, while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers:

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cyder-press, with patient look,

Thou watchest the last oozings hours by hours.

Where are the songs of spring? Ay, Where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,—

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

William Wordsworth, 1770-1850

Consider then also Wordsworth’s own quite divine personification of nature, and his unique portrayal of its sublime, transcendental beauty, the power of which is self evident from this - one of my favourite of his poems, a sonnet: Upon Westminster Bridge

Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802

Earth has not any thing to show more fair:

Dull would he be of soul who could pass by

A sight so touching in its majesty:

This City now doth, like a garment, wear

The beauty of the morning; silent, bare,

Ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

Never did sun more beautifully steep

In his first splendour, valley, rock, or hill;

Ne'er saw I, never felt, a calm so deep!

The river glideth at his own sweet will:

Dear God! the very houses seem asleep;

And all that mighty heart is lying still!

But then, moving on, once I had begun to expand the horizons a little, re-surface for that bit of air, rear the head out of that precious but quite specific window of literary lustre, it soon became evident as I sank deeper into the canon of English poetry - that rich, evocative imagery and far flung, poignant metaphor is prolific, everywhere – and well into either side of that period and beyond; and all begging for inclusion within the only too compact spheres of this bright but brief homage to greatness.

Of course this extends not only beyond the likes of Shakespeare, Donne and Milton, but you could say to more or less the whole raft of famed and accredited 19th, 20th and 21st century poets - including those right up to the present day, a number of whom are sitting right in front of our noses, as it were.

Poets Corner, Westminster Abbey

And so, at this juncture I would like to introduce the equally - if not more illustrious even - body of work of T.S. Eliot and his characteristic stark, ascetic Modernism that was to follow in the post Romantic, post WW1, aftermath.

While his standout poetry is too long to reproduce as such within the meagre voluministic confines of this site, you will find a series of excerpts from his works by clicking on the T.S. Eliot tab here or also in the Featured Poets section of this site.

Then take for example his unilaterally acclaimed masterpiece, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.

Consider the opening lines that compare the evening against the sky to a patient etherised upon a table; or also Wasteland (his own acerbic portrayal of the dystopia of 1920s London) - where he represents the sense of dissolution of the post-war generation, by founding his own innovative and quite complex structural form, seamlessly slipping between satire and prophecy, and frequently invoking abrupt changes of speaker, location and time.

T.S. Eliot, 1888-1965

Excerpt from The Waste Land

BY T. S. ELIOT

FOR EZRA POUND

IL MIGLIOR FABBRO

I. The Burial of the Dead

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.

Summer surprised us, coming over the Starnbergersee

With a shower of rain; we stopped in the colonnade,

And went on in sunlight, into the Hofgarten,

And drank coffee, and talked for an hour.

Bin gar keine Russin, stamm’ aus Litauen, echt deutsch.

And when we were children, staying at the arch-duke’s,

My cousin’s, he took me out on a sled,

And I was frightened. He said, Marie,

Marie, hold on tight. And down we went.

In the mountains, there you feel free.

I read, much of the night, and go south in the winter.

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images, where the sun beats,

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief,

And the dry stone no sound of water. Only

There is shadow under this red rock,

(Come in under the shadow of this red rock),

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.

1920s London, post WW1

Excerpt from The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

BY T. S. ELIOT

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table;

Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets,

The muttering retreats

Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels

And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells:

Streets that follow like a tedious argument

Of insidious intent

To lead you to an overwhelming question ...

Oh, do not ask, “What is it?”

Let us go and make our visit.

In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.

The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes,

The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the window-panes,

Licked its tongue into the corners of the evening,

Lingered upon the pools that stand in drains,

Let fall upon its back the soot that falls from chimneys,

Slipped by the terrace, made a sudden leap,

And seeing that it was a soft October night,

Curled once about the house, and fell asleep.

And indeed there will be time

For the yellow smoke that slides along the street,

Rubbing its back upon the window-panes;

There will be time, there will be time

To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet;

There will be time to murder and create,

And time for all the works and days of hands

That lift and drop a question on your plate;

Time for you and time for me,

And time yet for a hundred indecisions,

And for a hundred visions and revisions,

Before the taking of a toast and tea.

1920s London, gutter works

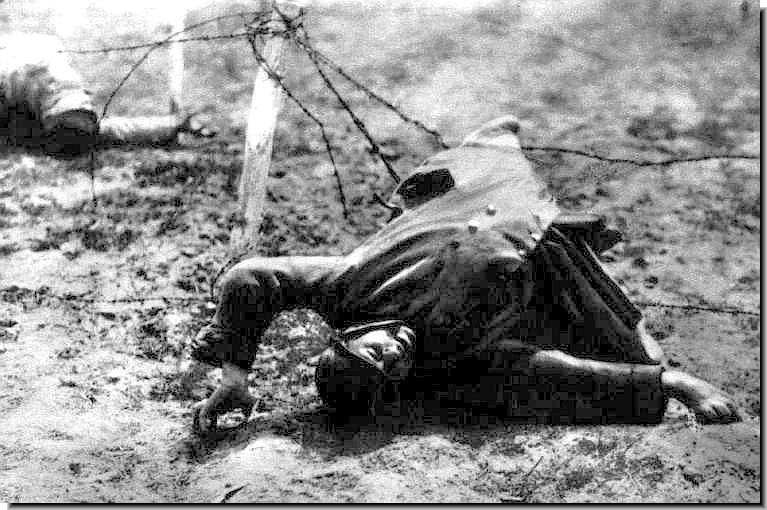

Wilfred Owen, 1893-1918

Next, moving on, or indeed - winding the clock back a decade - I think we owe it to the great genre of English language poetry, as if by rights, not to miss mention of Wilfred Owen - possibly the greatest war poet of all time.

Owen was influenced by the Romantics, and his poems are filled with the strong abounding resonances of his pararhyme, with which he raises the horrors and ironies of war.

Horrors of the Western Front

Consider also the brilliance, and the irony (below), with which he turns on its head Horace’s once sincere defence of Rome’s military cause, invoking high praise for Roman patriotism in the noble words ‘dulce et decorum est pro patria mori’ (‘it is a fine and honourable thing to die for your country’).

Owen composed nearly all of his work in slightly over a year, from August of 1917 aged 24 to September 1918, only to be killed in November 1918 one week before the Armistice.

Featured poems are “Anthem for Doomed Youth” and “Dulce Et Decorum Est’.

Anthem for Doomed Youth, by Wilfred Owen

Anthem for Doomed Youth

BY WILFRED OWEN

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

— Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles' rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells;

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs,—

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

What candles may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

The pallor of girls' brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

WW1 Gas Attack

Dulce et Decorum Est

BY WILFRED OWEN

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

“DULCE ET DECORUM EST”

(Roads Cenotaph)

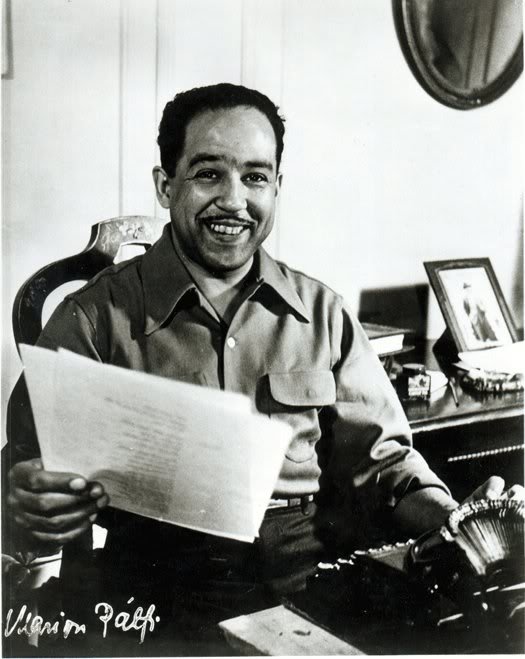

Whilst in the same decade there was something quite different going on altogether in Harlem, New York – then the burgeoning Mecca for young people of black origin growing up in the US, and internationally (note the “Harlem Renaissance” was celebrated worldwide as the flowering of black intellectual, literary and artistic life).

The Cotton Club, Harlem New York

Here was founded a type of rhythm and music - Blues and Jazz - in which there was a sense of oppression from the legacy of slave culture in the US, but at the same time a sense of indulgence and hope in the music, in turn connected to the vibrancy of the city itself – and it is here that we come to the powerful, emotive words and sound of Langston Hughes.

Langston Hughes, 1901-1967

Langston Hughes’ poetry focused on a kind of catharsis of the negro pain - achieved through the music of the poetry, where there is a real tension between sadness and at the same time a kind of onward intoxication in the music of the poem; famously captured in The Weary Blues where the rhythm and sounds of the words are indelibly intertwined with the mood and the meaning.

Featured poem: The Weary Blues

The Weary Blues

Droning a drowsy syncopated tune,

Rocking back and forth to a mellow croon,

I heard a Negro play.

Down on Lenox Avenue the other night

By the pale dull pallor of an old gas light

He did a lazy sway. . . .

He did a lazy sway. . . .

To the tune o’ those Weary Blues.

With his ebony hands on each ivory key

He made that poor piano moan with melody.

O Blues!

Swaying to and fro on his rickety stool

He played that sad raggy tune like a musical fool.

Sweet Blues!

Coming from a black man’s soul.

O Blues!

In a deep song voice with a melancholy tone

I heard that Negro sing, that old piano moan—

“Ain’t got nobody in all this world,

Ain’t got nobody but ma self.

I’s gwine to quit ma frownin’

And put ma troubles on the shelf.”

Thump, thump, thump, went his foot on the floor.

He played a few chords then he sang some more—

“I got the Weary Blues

And I can’t be satisfied.

Got the Weary Blues

And can’t be satisfied—

I ain’t happy no mo’

And I wish that I had died.”

And far into the night he crooned that tune.

The stars went out and so did the moon.

The singer stopped playing and went to bed

While the Weary Blues echoed through his head.

He slept like a rock or a man that’s dead.

William Butler Yeats, 1865-1939

And next we come to William Butler Yeats, who is perhaps the most exquisite of all in terms of the charm, the sounds and the musicality that his words produce, and he is widely acknowledged as one of the greatest poets in the history of the language.

Yeats lived in London for much of his early childhood, but was all the while staunchly self-affirmed in his ardent loyalty to the indigenous Ireland of his birth, and then again to its rich Gaelic linguistic and artistic roots and heritage.

Master of the traditional form, Yeats through the course of his life transitioned from an ornate lyricism to a realism and then social irony, and then eventually to spiritualism, filled with symbolism and metaphysics.

He was awarded the Nobel prize for literature in 1923 “for his always inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation [Ireland]”

( <http://www.nobelprize.org> ).

Perhaps no other poet stood to represent a people and a country as poignantly as Yeats.

Featured poems by Yeats: Leda and the Swan, & Lake Isle of Innisfree

Leda and the Swan

A sudden blow: the great wings beating still

Above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed

By the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill,

He holds her helpless breast upon his breast.

How can those terrified vague fingers push

The feathered glory from her loosening thighs?

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?

A shudder in the loins engenders there

The broken wall, the burning roof and tower

And Agamemnon dead.

Being so caught up,

So mastered by the brute blood of the air,

Did she put on his knowledge with his power

Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?

The Lake Isle of Innisfree

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made;

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

Allen Ginsberg, 1926-1997

And then, of any compilation that includes the seminal excerpts of 20th century poetry, it would have to include - again by rights - Allen Ginsberg’s, and his extraordinary, rule and ground-breaking masterpiece Howl.

Ginsberg, together with Kerouac and Burroughs – aka the Beat Generation poets – pioneered the concept of ‘spontaneous prose’, the idea that literature should come from the soul unfiltered.

Ginsberg’s poetry was influenced by American Modernism, but also by Romanticism, as well as the beat and the cadences of jazz poetry (notably the bop rhythm of Charlie Parker), and then also his (Ginsberg’s) own Kagyu Buddhist practice and Jewish background. He considered himself to have inherited the visionary, poetic mantle handed down from Blake, Whitman and Federico Garcia Lorca.

“The power of Ginsberg’s verse, its probing focus, its long and lilting lines, as well as its new world exuberance all echo the continuity of inspiration that he claimed.” (Wikipedia)

Ginsberg opposed war, materialism and sexual repression, was hostile to bureaucracy and open to Eastern religions.

In Howl he denounces the destructive forces of Capitalism and Conformity in the US. The poem was seized in 1956 by San Francisco police and US Customs, and later in 1957 was the subject of an obscenity trial. Judge Clayton W. Horn ruled however that it was not obscene: “Would there be any freedom of press or speech if one must reduce the vocabulary to vapid innocuous euphemisms?” he said.

Featured is an excerpt from Howl, and the (full) poem America

Excerpt from “Howl”

For Carl Solomon

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night,

who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat up smoking in the supernatural darkness of cold-water flats floating across the tops of cities contemplating jazz,

who bared their brains to Heaven under the El and saw Mohammedan angels staggering on tenement roofs illuminated,

who passed through universities with radiant cool eyes hallucinating Arkansas and Blake-light tragedy among the scholars of war,

who were expelled from the academies for crazy & publishing obscene odes on the windows of the skull,

who cowered in unshaven rooms in underwear, burning their money in wastebaskets and listening to the Terror through the wall,

who got busted in their pubic beards returning through Laredo with a belt of marijuana for New York,

who ate fire in paint hotels or drank turpentine in Paradise Alley, death, or purgatoried their torsos night after night

with dreams, with drugs, with waking nightmares, alcohol and cock and endless balls,

incomparable blind streets of shuddering cloud and lightning in the mind leaping toward poles of Canada & Paterson, illuminating all the motionless world of Time between,

Peyote solidities of halls, backyard green tree cemetery dawns, wine drunkenness over the rooftops, storefront boroughs of teahead joyride neon blinking traffic light, sun and moon and tree vibrations in the roaring winter dusks of Brooklyn, ashcan rantings and kind king light of mind,

who chained themselves to subways for the endless ride from Battery to holy Bronx on benzedrine until the noise of wheels and children brought them down shuddering mouth-wracked and battered bleak of brain all drained of brilliance in the drear light of Zoo,

who sank all night in submarine light of Bickford’s floated out and sat through the stale beer afternoon in desolate Fugazzi’s, listening to the crack of doom on the hydrogen jukebox,

who talked continuously seventy hours from park to pad to bar to Bellevue to museum to the Brooklyn Bridge,

a lost battalion of platonic conversationalists jumping down the stoops off fire escapes off windowsills off Empire State out of the moon,

yacketayakking screaming vomiting whispering facts and memories and anecdotes and eyeball kicks and shocks of hospitals and jails and wars,

whole intellects disgorged in total recall for seven days and nights with brilliant eyes, meat for the Synagogue cast on the pavement,

who vanished into nowhere Zen New Jersey leaving a trail of ambiguous picture postcards of Atlantic City Hall,

suffering Eastern sweats and Tangerian bone-grindings and migraines of China under junk-withdrawal in Newark’s bleak furnished room,

who wandered around and around at midnight in the railroad yard wondering where to go, and went, leaving no broken hearts,

who lit cigarettes in boxcars boxcars boxcars racketing through snow toward lonesome farms in grandfather night,

who studied Plotinus Poe St. John of the Cross telepathy and bop kabbalah because the cosmos instinctively vibrated at their feet in Kansas,

who loned it through the streets of Idaho seeking visionary indian angels who were visionary indian angels,

who thought they were only mad when Baltimore gleamed in supernatural ecstasy,

who jumped in limousines with the Chinaman of Oklahoma on the impulse of winter midnight streetlight smalltown rain,

who lounged hungry and lonesome through Houston seeking jazz or sex or soup, and followed the brilliant Spaniard to converse about America and Eternity, a hopeless task, and so took ship to Africa,

who disappeared into the volcanoes of Mexico leaving behind nothing but the shadow of dungarees and the lava and ash of poetry scattered in fireplace Chicago,

who reappeared on the West Coast investigating the FBI in beards and shorts with big pacifist eyes sexy in their dark skin passing out incomprehensible leaflets,

who burned cigarette holes in their arms protesting the narcotic tobacco haze of Capitalism,

who distributed Supercommunist pamphlets in Union Square weeping and undressing while the sirens of Los Alamos wailed them down, and wailed down Wall, and the Staten Island ferry also wailed,

who broke down crying in white gymnasiums naked and trembling before the machinery of other skeletons,

who bit detectives in the neck and shrieked with delight in policecars for committing no crime but their own wild cooking pederasty and intoxication,

who howled on their knees in the subway and were dragged off the roof waving genitals and manuscripts,

who let themselves be fucked in the ass by saintly motorcyclists, and screamed with joy,

who blew and were blown by those human seraphim, the sailors, caresses of Atlantic and Caribbean love,

(end of excerpt…)

America

America I’ve given you all and now I’m nothing.

America two dollars and twentyseven cents January 17, 1956.

I can’t stand my own mind.

America when will we end the human war?

Go fuck yourself with your atom bomb.

I don’t feel good don’t bother me.

I won’t write my poem till I’m in my right mind.

America when will you be angelic?

When will you take off your clothes?

When will you look at yourself through the grave?

When will you be worthy of your million Trotskyites?

America why are your libraries full of tears?

America when will you send your eggs to India?

I’m sick of your insane demands.

When can I go into the supermarket and buy what I need with my good looks?

America after all it is you and I who are perfect not the next world.

Your machinery is too much for me.

You made me want to be a saint.

There must be some other way to settle this argument.

Burroughs is in Tangiers I don’t think he’ll come back it’s sinister.

Are you being sinister or is this some form of practical joke?

I’m trying to come to the point.

I refuse to give up my obsession.

America stop pushing I know what I’m doing.

America the plum blossoms are falling.

I haven’t read the newspapers for months, everyday somebody goes on trial for murder.

America I feel sentimental about the Wobblies.

America I used to be a communist when I was a kid I’m not sorry.

I smoke marijuana every chance I get.

I sit in my house for days on end and stare at the roses in the closet.

When I go to Chinatown I get drunk and never get laid.

My mind is made up there’s going to be trouble.

You should have seen me reading Marx.

My psychoanalyst thinks I’m perfectly right.

I won’t say the Lord’s Prayer.

I have mystical visions and cosmic vibrations.

America I still haven’t told you what you did to Uncle Max after he came over from Russia.

I’m addressing you.

Are you going to let your emotional life be run by Time Magazine?

I’m obsessed by Time Magazine.

I read it every week.

Its cover stares at me every time I slink past the corner candystore.

I read it in the basement of the Berkeley Public Library.

It’s always telling me about responsibility. Businessmen are serious. Movie producers are serious. Everybody’s serious but me.

It occurs to me that I am America.

I am talking to myself again.

Asia is rising against me.

I haven’t got a chinaman’s chance.

I’d better consider my national resources.

My national resources consist of two joints of marijuana millions of genitals an unpublishable private literature that jetplanes 1400 miles an hour and twentyfive-thousand mental institutions.

I say nothing about my prisons nor the millions of underprivileged who live in my flowerpots under the light of five hundred suns.

I have abolished the whorehouses of France, Tangiers is the next to go.

My ambition is to be President despite the fact that I’m a Catholic.

America how can I write a holy litany in your silly mood?

I will continue like Henry Ford my strophes are as individual as his automobiles more so they’re all different sexes.

America I will sell you strophes $2500 apiece $500 down on your old strophe

America free Tom Mooney

America save the Spanish Loyalists

America Sacco & Vanzetti must not die

America I am the Scottsboro boys.

America when I was seven momma took me to Communist Cell meetings they sold us garbanzos a handful per ticket a ticket costs a nickel and the speeches were free everybody was angelic and sentimental about the workers it was all so sincere you have no idea what a good thing the party was in 1835 Scott Nearing was a grand old man a real mensch Mother Bloor the Silk-strikers’ Ewig-Weibliche made me cry I once saw the Yiddish orator Israel Amter plain. Everybody must have been a spy.

America you don’t really want to go to war.

America its them bad Russians.

Them Russians them Russians and them Chinamen. And them Russians.

The Russia wants to eat us alive. The Russia’s power mad. She wants to take our cars from out our garages.

Her wants to grab Chicago. Her needs a Red Reader’s Digest. Her wants our auto plants in Siberia. Him big bureaucracy running our fillingstations.

That no good. Ugh. Him make Indians learn read. Him need big black niggers. Hah. Her make us all work sixteen hours a day. Help.

America this is quite serious.

America this is the impression I get from looking in the television set.

America is this correct?

I’d better get right down to the job.

It’s true I don’t want to join the Army or turn lathes in precision parts factories, I’m nearsighted and psychopathic anyway.

America I’m putting my queer shoulder to the wheel.

Berkeley, January 17, 1956

Sylvia Plath, 1932-1963

Next we must pay homage to Sylvia Plath - and her serene, gracile adroitness, who in the mid 20th century created simply electric combinations of violent and disturbed imagery - coupled with a playful use of alliteration and rhyme, all produced within a sheer virtuosity of form.

Clinically depressed for most of her adult life, she was treated on multiple occasions with electroconvulsive therapy. And then she killed herself in 1963.

She was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer prize in 1982.

Featured poems are The Colossus, & Crossing the Water

The Colossus

BY SYLVIA PLATH

I shall never get you put together entirely,

Pieced, glued, and properly jointed.

Mule-bray, pig-grunt and bawdy cackles

Proceed from your great lips.

It’s worse than a barnyard.

Perhaps you consider yourself an oracle,

Mouthpiece of the dead, or of some god or other.

Thirty years now I have labored

To dredge the silt from your throat.

I am none the wiser.

Scaling little ladders with glue pots and pails of lysol

I crawl like an ant in mourning

Over the weedy acres of your brow

To mend the immense skull plates and clear

The bald, white tumuli of your eyes.

A blue sky out of the Oresteia

Arches above us. O father, all by yourself

You are pithy and historical as the Roman Forum.

I open my lunch on a hill of black cypress.

Your fluted bones and acanthine hair are littered

In their old anarchy to the horizon-line.

It would take more than a lightning-stroke

To create such a ruin.

Nights, I squat in the cornucopia

Of your left ear, out of the wind,

Counting the red stars and those of plum-color.

The sun rises under the pillar of your tongue.

My hours are married to shadow.

No longer do I listen for the scrape of a keel

On the blank stones of the landing.

Crossing The Water

BY SYLVIA PLATH

Black lake, black boat, two black, cut-paper people.

Where do the black trees go that drink here?

Their shadows must cover Canada.

A little light is filtering from the water flowers.

Their leaves do not wish us to hurry:

They are round and flat and full of dark advice.

Cold worlds shake from the oar.

The spirit of blackness is in us, it is in the fishes.

A snag is lifting a valedictory, pale hand;

Stars open among the lilies.

Are you not blinded by such expressionless sirens?

This is the silence of astounded souls.

Dorothy Parker, 1893-1967

At this point I’d like to turn back a couple of decades once again, so as not to fail mention of the seminal, and uniquely vicious and acerbic wit of Dorothy Parker.

Enough Rope, her first volume of poetry published in 1926, was initially dismissed by the New York Times as ‘flapper verse’ yet her collection sold 47,000 copies, receiving impressive reviews everywhere else, and her work has endured.

Her poetry was “caked with a salty humor, rough with splinters of dissolution and tarred with a bright black authenticity” (The Nation).

In her case I think you need a taste of her poetry first hand in order to really get the gist of her insertion here (within the aforesaid compact spheres of this compendium of undivided artistic wizardry, and the even more compact confines of this its introduction so to speak).

But then again, consider if only the titles of some of her other works, such as for example Sunset Gun (1928), Death & Taxes (1931), Laments for the Living, and Not So Deep as a Well.

Featured poems (below): Autumn Valentine, Transition, Ballade at Thirty Five, The Danger of Writing Defiant Verse, Unfortunate Coincidence, & Interview

Dorothy Parker

Autumn Valentine

In May my heart was breaking-

Oh, wide the wound, and deep!

And bitter it beat at waking,

And sore it split in sleep.

And when it came November,

I sought my heart, and sighed,

"Poor thing, do you remember?"

"What heart was that?" it cried.

Transition

Too long and quickly have I lived to vow

The woe that stretches me shall never wane,

Too often seen the end of endless pain

To swear that peace no more shall cool my brow.

I know, I know- again the shriveled bough

Will burgeon sweetly in the gentle rain,

And these hard lands be quivering with grain-

I tell you only: it is Winter now.

What if I know, before the Summer goes

Where dwelt this bitter frenzy shall be rest?

What is it now, that June shall surely bring

New promise, with the swallow and the rose?

My heart is water, that I first must breast

The terrible, slow loveliness of Spring.

Ballade at Thirty Five

This, no song of an ingénue,

This, no ballad of innocence;

This, the rhyme of a lady who

Followed ever her natural bents.

This, a solo of sapience,

This, a chantey of sophistry,

This, the sum of experiments, --

I loved them until they loved me.

Decked in garments of sable hue,

Daubed with ashes of myriad Lents,

Wearing shower bouquets of rue,

Walk I ever in penitence.

Oft I roam, as my heart repents,

Through God's acre of memory,

Marking stones, in my reverence,

"I loved them until they loved me."

Pictures pass me in long review,--

Marching columns of dead events.

I was tender, and, often, true;

Ever a prey to coincidence.

Always knew I the consequence;

Always saw what the end would be.

We're as Nature has made us -- hence

I loved them until they loved me.

The Danger of Writing Defiant Verse

And now I have another lad!

No longer need you tell

How all my nights are slow and sad

For loving you too well.

His ways are not your wicked ways,

He's not the like of you.

He treads his path of reckoned days,

A sober man, and true.

They'll never see him in the town,

Another on his knee.

He'd cut his laden orchards down,

If that would pleasure me.

He'd give his blood to paint my lips

If I should wish them red.

He prays to touch my finger-tips

Or stroke my prideful head.

He never weaves a glinting lie,

Or brags the hearts he'll keep.

I have forgotten how to sigh—

Remembered how to sleep.

He's none to kiss away my mind—

A slower way is his.

Oh, Lord! On reading this, I find

A silly lot he is.

Unfortunate Coincidence

by DOROTHY PARKER

By the time you swear you're his,

Shivering and sighing,

And he vows his passion is

Infinite, undying -

Lady, make a note of this:

One of you is lying.

Interview

The ladies men admire, I’ve heard,

Would shudder at a wicked word.

Their candle gives a single light;

They’d rather stay at home at night.

They do not keep awake till three,

Nor read erotic poetry.

They never sanction the impure,

Nor recognize an overture.

They shrink from powders and from paints ...

So far, I’ve had no complaints.

Gwendolyn Brooks, 1917-2000

And now I would also like to specially pick out Gwendolyn Brooks, and her famously authentic, textured portraits of the struggles of ordinary people in her community - characters drawn from the inner city life of Bronzeville (Ilinois) that she knew only too well.

Brooks was Poet Laureate of Ilinois and the first African American to win the Pulitzer prize (1950), “She takes hold of reality as it is and renders it faithfully … she easily catches the pathos of petty destinies; the whimper of the wounded; and the tiny accidents that plague the lives of the desperately poor” (source: Wikipedia).

Featured poems: Kitchenette Building, Jessie Mitchell’s Mother, The Mother, & Sadie and Maud

Kitchenette Building

We are things of dry hours and the involuntary plan,

Grayed in, and gray. “Dream” makes a giddy sound, not strong

Like “rent,” “feeding a wife,” “satisfying a man.”

But could a dream send up through onion fumes

Its white and violet, fight with fried potatoes

And yesterday’s garbage ripening in the hall,

Flutter, or sing an aria down these rooms

Even if we were willing to let it in,

Had time to warm it, keep it very clean,

Anticipate a message, let it begin?

We wonder. But not well! not for a minute!

Since Number Five is out of the bathroom now,

We think of lukewarm water, hope to get in it.

Jessie Mitchell’s Mother

Into her mother’s bedroom to wash the ballooning body.

“My mother is jelly-hearted and she has a brain of jelly:

Sweet, quiver-soft, irrelevant. Not essential.

Only a habit would cry if she should die.

A pleasant sort of fool without the least iron. . . .

Are you better, mother, do you think it will come today?”

The stretched yellow rag that was Jessie Mitchell’s mother

Reviewed her. Young, and so thin, and so straight.

So straight! as if nothing could ever bend her.

But poor men would bend her, and doing things with poor men,

Being much in bed, and babies would bend her over,

And the rest of things in life that were for poor women,

Coming to them grinning and pretty with intent to bend and to kill.

Comparisons shattered her heart, ate at her bulwarks:

The shabby and the bright: she, almost hating her daughter,

Crept into an old sly refuge: “Jessie’s black

And her way will be black, and jerkier even than mine.

Mine, in fact, because I was lovely, had flowers

Tucked in the jerks, flowers were here and there. . . .”

She revived for the moment settled and dried-up triumphs,

Forced perfume into old petals, pulled up the droop,

Refueled

Triumphant long-exhaled breaths.

Her exquisite yellow youth . . .

The Mother

Abortions will not let you forget.

You remember the children you got that you did not get,

The damp small pulps with a little or with no hair,

The singers and workers that never handled the air.

You will never neglect or beat

Them, or silence or buy with a sweet.

You will never wind up the sucking-thumb

Or scuttle off ghosts that come.

You will never leave them, controlling your luscious sigh,

Return for a snack of them, with gobbling mother-eye.

I have heard in the voices of the wind the voices of my dim killed

children.

I have contracted. I have eased

My dim dears at the breasts they could never suck.

I have said, Sweets, if I sinned, if I seized

Your luck

And your lives from your unfinished reach,

If I stole your births and your names,

Your straight baby tears and your games,

Your stilted or lovely loves, your tumults, your marriages, aches,

and your deaths,

If I poisoned the beginnings of your breaths,

Believe that even in my deliberateness I was not deliberate.

Though why should I whine,

Whine that the crime was other than mine?—

Since anyhow you are dead.

Or rather, or instead,

You were never made.

But that too, I am afraid,

Is faulty: oh, what shall I say, how is the truth to be said?

You were born, you had body, you died.

It is just that you never giggled or planned or cried.

Believe me, I loved you all.

Believe me, I knew you, though faintly, and I loved, I loved you

All.

Sadie and Maud

Maud went to college.

Sadie stayed home.

Sadie scraped life

With a fine toothed comb.

She didn’t leave a tangle in

Her comb found every strand.

Sadie was one of the livingest chicks

In all the land.

Sadie bore two babies

Under her maiden name.

Maud and Ma and Papa

Nearly died of shame.

When Sadie said her last so-long

Her girls struck out from home.

(Sadie left as heritage

Her fine-toothed comb.)

Maud, who went to college,

Is a thin brown mouse.

She is living all alone

In this old house.

James Berry, 1924-2017

At this juncture I would also like to highlight the poetry of James Berry and his signature graphic, powerfully evocative intertwining of the Standard English with the Jamaican patois.

James Berry was born in rural Portland, Jamaica and after some years in the US settled in Britain in 1948 - and it is in that magnetic dialect that he explores the excitement and tensions of the evolving Caribbean community with indigenous Britain in the 1940s onwards. Again for me, as in the poetry of Langston Hughes, the beauty of the sound and the rhythm is self-evident, seeped in its wonderful, mesmerising cadences.

Featured poems: The Outsider, & Englan Voice

The Outsider

by JAMES BERRY

If you see me lost on busy streets,

my dazzle is sun-stain of skin,

I’m not naked with dark glasses on

saying barren ground has no oasis:

it’s that cracked up by extremes

I must hold self

together with extreme pride.

If you see me lost in neglected

woods, I’m no thief eyeing trees

to plunder their stability

or a moaner shouting at air:

it’s that voices in me rule

firmer than my skills, and sometimes

among men my stubborn hurts

leave me like wild dogs.

If you see me lost on forbidding

wastelands, watching dry flowers

nod, or scraping a tunnel

in mountain rocks, I don’t open

a trail back into time:

it’s that a monotony

like the Sahara seals my enchantment.

If you see me lost on long

footpaths, I don’t set traps

or map out arable acres:

it’s that I must exhaust twigs

like limbs with water divining.

If you see me lost in my sparse

room, I don’t ruminate

on prisoners and falsify

their jokes, and go on about

prisons having been perfected

like a common smokescreen of mind:

it’s that I moved

my circle from ruins

and I search to remake it whole.

Englan Voice

by JAMES BERRY

I prepare – an prepare well – fe Englan.

Me decide, and done leave behine

all the voice of ol slave-estate bushman.

None of that distric bad-talk in Englan,

that bush talk of ol slave-estate man.

Hear me speak in Englan, an see

you dohn think I a Englan native.

Me nah go say ‘Bwoy, how you du?'

me a-go say 'How are you old man?'

Me nah go say

'Wha yu nyam las night?'

me a-go say “What did you have for supper?'

Patois talk is bushman talk –

people who talk patois them dam lazy.

Because mi bush voice so settle in me

an might let me down in-a Englan

me a-practise.

Me a-practise talk like teacher

till mi Englan voice come out-a me

like water from hillside rock.

Even if you fellows here

dohn hear mi Englan voice

I have it - an hear it in mi head!

William Shakespeare, 1564-1616

And now, as we approach the denouement of this hallowed introduction to aforesaid homage to great and seminal poetry, for its penultimate entry [all the while noting however that there is also a fuller and more thorough offering of great poets and their poems in the ‘Featured Poets’ section of this site] - I would like to wind back the clock a few centuries, to somewhere closer to where it all began.

So let us now pay our respects and- genuflections- to one who is possibly the greatest sonnet writer, playright and literary genius in the history of the language itself, and one who needs no introduction - for it is the great bard of Avon himself, William Shakespeare.

As an quizzical fact, on the subject of poetry, in his plays Shakespeare was a satiric critic of sonnets – his allusions to them are often scornful. But then in 1609 he goes on to publish a full collection of 154 sonnets, one of the longest sonnet sequences of his era. While they may be considered a continuation of the sonnet tradition that swept throughout the Renaissance from Petrach in 14th century Italy through its introduction into 16th century England by Thomas Wyatt, Shakespeare’s sonnets mark such a significant departure in terms of content that they would almost rebel against that then well-worn 200 years old tradition. Instead of expressing worshipful love for a goddess-like yet unobtainable female love object, as Petrarch and Dante had done, Shakespeare introduces a young man. He also introduces a Dark Lady (who is no goddess) and explores themes such as lust, homoeroticism, misogyny, infidelity, and acrimony in ways that challenged, but also opened up new terrain for the sonnet form.

Featured sonnets: Sonnet 18 “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?’, & Sonnet 116 “Let me not to the marriage of true minds”

Sonnet 18 “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed,

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature’s changing course untrimmed:

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st,

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

Sonnet 116 “Let me not to the marriage of true minds”

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove:

O, no! it is an ever-fixed mark,

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wandering bark,

Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken.

Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle’s compass come;

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.

If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

John Donne, 1572-1631

And then, to finally in truth conclude this introduction to quintessential and mesmerising English language poetry, the last mention is reserved for no less than John Donne (1572-1631), leading English poet of the Metaphysical school, famed for his use of conceits (elaborate, far-fetched, extended metaphors), and is considered probably the greatest love poet in the English language.

Donne’s poems were marked by their immense knowledge of English society and a sharp criticism of its problems. Amongst other things his satires deal with corruption in the legal system, mediocre poets, pompous courtiers, reflecting his view of a society filled with fools and knaves. He also deals with the problem of true religion – a matter of great importance to him. He argues that it is better to examine carefully one’s religious convictions than blindly to follow any established tradition, for none would be saved at the Final Judgement.

Featured poems: The Flea, The Good Morrow, & Death Be Not Proud

The Flea:-

by JOHN DONNE

Mark but this flea, and mark in this,

How little that which thou deniest me is;

It sucked me first, and now sucks thee,

And in this flea our two bloods mingled be;

Thou know’st that this cannot be said

A sin, nor shame, nor loss of maidenhead,

Yet this enjoys before it woo,

And pampered swells with one blood made of two,

And this, alas, is more than we would do.

Oh stay, three lives in one flea spare,

Where we almost, nay more than married are.

This flea is you and I, and this

Our marriage bed, and marriage temple is;

Though parents grudge, and you, w'are met,

And cloistered in these living walls of jet.

Though use make you apt to kill me,

Let not to that, self-murder added be,

And sacrilege, three sins in killing three.

Cruel and sudden, hast thou since

Purpled thy nail, in blood of innocence?

Wherein could this flea guilty be,

Except in that drop which it sucked from thee?

Yet thou triumph’st, and say'st that thou

Find’st not thy self, nor me the weaker now;

’Tis true; then learn how false, fears be:

Just so much honor, when thou yield’st to me,

Will waste, as this flea’s death took life from thee.

The Good Morrow:-

by JOHN DONNE

I wonder, by my troth, what thou and I

Did, till we loved? Were we not weaned till then?

But sucked on country pleasures, childishly?

Or snorted we in the Seven Sleepers’ den?

’Twas so; but this, all pleasures fancies be.

If ever any beauty I did see,

Which I desired, and got, ’twas but a dream of thee.

And now good-morrow to our waking souls,

Which watch not one another out of fear;

For love, all love of other sights controls,

And makes one little room an everywhere.

Let sea-discoverers to new worlds have gone,

Let maps to other, worlds on worlds have shown,

Let us possess one world, each hath one, and is one.

My face in thine eye, thine in mine appears,

And true plain hearts do in the faces rest;

Where can we find two better hemispheres,

Without sharp north, without declining west?

Whatever dies, was not mixed equally;

If our two loves be one, or, thou and I

Love so alike, that none do slacken, none can die.

Death Be Not Proud

by JOHN DONNE

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

For those whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be,

Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee do go,

Rest of their bones, and soul’s delivery.

Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell,

And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well

And better than thy stroke; why swell’st thou then?

One short sleep past, we wake eternally

And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

And, recapturing the earlier theme of Romanticism (work of the Romantic period in the 19th century - or of a like minded sensibility, that is), here are some examples of Romantic works of art:

The Course of Empire, example of a Romantic work of art

by Thomas Cole, 1833-36

The Shipwreck, example of a Romantic work of art

by Claude Joseph Vernet, 1759

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, example of a Romantic work of art

by Caspar David Friedrich, 1818

A Romantic painting by J.W.M. Turner inspired by the Romantic poem “I would I were a careless child”