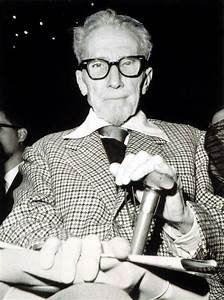

Ezra Pound

Ezra Pound, 1885–1972

Poet Ezra Pound authored more than 70 books and promoted many other now-famous writers, including James Joyce and T.S. Eliot.

Who Was Ezra Pound?

Poet Ezra Pound studied literature and languages in college and in 1908 left for Europe, where he published several successful books of poetry. Pound advanced a "modern" movement in English and American literature. His pro-Fascist broadcasts in Italy during World War II led to his arrest and confinement until 1958.

Early Years and Career

Pound was born in the small mining town of Hailey, Idaho, on October 30, 1885. The only child of Homer Loomis Pound, a Federal Land Office official, and his wife, Isabel, Ezra spent the bulk of his childhood just outside Philadelphia, where his father had moved the family after accepting a job with the U.S. Mint. His childhood seems to have been a happy one. He eventually attended Cheltenham Military Academy, staying there two years before leaving to finish his high school education at a local public school.

In 1901, Pound enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania, but left after two years and transferred to Hamilton College in Clinton, New York, where he earned a bachelor's degree in philosophy. By this time, Pound knew full well that he wanted to be a poet. At the age of 15, he had told his parents as much. Though his chosen vocation certainly wasn't something he had inherited directly from his more conventional mother and father, Homer and Isabel were supportive of their son's choice.

In 1907, after finishing college, Pound accepted a teaching job at Indiana's Wabash College. But the fit between the artistic, somewhat bohemian poet and the formal institution was less than perfect, and Pound soon left.

His next move proved to be more daring. In 1908, with just $80 in his pocket, he set sail for Europe and landed in Venice brimming with confidence that he would soon make a name for himself in the world of poetry. With his own money, Pound paid for the publication of his first book of poems, "A Lume Spento."

Despite the fact that the work did not create the kind of fireworks he had hoped for, it did open some important doors for him. In late 1908, Pound traveled to London, where he befriended the influential writer and editor Ford Madox Ford, as well as William Butler Yeats. His friendship with Yeats, in particular, was a close one, and Pound eventually took a job as the writer's secretary, and later served as best man at his wedding.

Success Abroad

In 1909, Pound found the kind of success as a writer that he had wanted. Over the next year, he produced three books, Personae, Exultations and The Spirit of Romance, the last one based on the lectures he had given in London. All three books were warmly received. Wrote one reviewer that Pound "is that rare thing among modern poets, a scholar."

In addition, Pound wrote numerous reviews and critiques for a variety of publications, such as New Age, The Egoist and Poetry. As his friend T.S. Eliot would later note, "During a crucial decade in the history of modern literature, approximately 1912–1922, Pound was the most influential and in some ways the best critic in England or America."

In 1912, Pound helped create a movement that he and others called "Imagism," which signaled a new literary direction for the poet. At the core of Imagism, was a push to set a more direct course with language, shedding the sentiment that had so wholly shaped Victorian and Romantic poetry.

Precision and economy were highly valued by Pound and the other proponents of the movement, which included F.S. Flint, William Carlos Williams, Amy Lowell, Richard Aldington and Hilda Doolittle. With its focus on the "thing" as the "thing," Imagism reflected the changes happening in other art forms, most notably painting and the Cubists.

Pound's maxims included, "Do not retell in mediocre verse what has already been done in good prose" and "Use no superfluous word, no adjective which does not reveal something." But Pound's connection to Imagism was short-lived. After just a few years, he stepped aside, frustrated when he couldn't secure total control of the movement from Lowell and the others.

Famous Friendships

Pound's influence extended in other directions. He had an incredible eye for talent and tirelessly promoted writers whose works he felt demanded attention. He introduced the world to up-and-coming poets like Robert Frost and D.H. Lawrence, and was Eliot's editor. In fact, it was Pound who edited Eliot's "The Waste Land," which many consider to be one of the greatest poems produced during the modernist era.

Over the years, Pound and Eliot would become great friends. Early in his career, when Eliot abandoned his graduate studies in philosophy at Oxford, it was Pound who wrote the young poet's parents to break the news to them.

Pound's lineup of friends also included the Irish novelist James Joyce, whom he helped introduce to publishers and find landing spots in magazines for several of the stories in "The Dubliners" and "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man." During Joyce's leanest years, Pound helped him with money and even, it is said, helped secure for him an old pair of shoes to wear.

'The Cantos'

Pound's own work continued to flourish as well. The years immediately following World War I saw the production of two of his most admired works, "Homage to Sextus Propertius" (1919) and the 18-part "Hugh Selwyn Mauberley" (1921), the latter of which tackled a wide range of subjects, from the artist and society to the horrors of mass production and World War I.

In late 1920, after 12 years in London, Pound left England for a new start in Paris. But his tolerance for French life, it seems, was limited. In 1924, tired of the Parisian scene, Pound moved again, this time settling in the Italian city of Rapallo, where he would remain for the next two decades. It was here that Pound's life changed significantly. In 1925, he had a daughter, Maria, with American violinist Olga Rudge, and the following year he had a son, Omar, with his wife, Dorothy.

Professionally, Pound had turned his full attention to "The Cantos," an ambitious long- form poem he had begun in 1915. A work he self-described as his "poem including history," "The Cantos" revealed Pound's interest in economics and in the world's changing financial landscape in the wake of World War I.

The first section of the poem was published in 1925, with later editions appearing later ("Eleven New Cantos," 1934; "The Fifth Decade of Cantos," 1937; "Cantos LII-LXXI," 1940).

Fascist Connections

As Pound's interest in economics and economic history increased, he showed his support for the theories of Major C.H. Douglas, the founder of Social Credit, an economic theory that believed that the poor distribution of wealth was due to insufficient purchasing power on the part of governments. Pound began to see a world of injustice shaped by international bankers, whose manipulation of money led to wars and conflict.

Pound's impassioned feelings on the matter soon led him to support the Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini. In 1939, Pound visited the United States in the hope that he could help prevent war between his native country and his adopted one. But success eluded him, and upon his return to Italy, Pound set out recording hundreds of broadcasts for Rome Radio in which he threw his support behind Mussolini, condemned the United States, and claimed that a group of Jewish bankers had directed America into war.

In 1945, partisans arrested Pound and handed him over to U.S. Forces, who held him for six months at a detention center outside Pisa. He was then flown back to the United States to stand trial for treason, but was found to be insane and was directed to St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington DC, where he remained until 1958.

Pound's exact state of mind during this time has come into question over the years. In the early 1980s, a full decade after Pound's death, a professor of American Institutions at the University of Wisconsin presented evidence that Pound was indeed sane enough to stand trial for treason. However, it was certainly true that Pound was healthy enough to work. During his imprisonment in Italy he finished the "Pisan Cantos," which The New York Times praised as "among the masterpieces of the century."

Pound continued to write during his confinement at St. Elizabeths as well. There he completed additional sections of his long poem, "Section: Rock-Drill," published in 1955, and "Thrones," which appeared in 1959.

In 1958, Frost spearheaded a successful campaign to free Pound from the comfortable confines of St. Elizabeths. Pound returned to Italy immediately, and in 1969, published "Drafts and Fragments of Cantos CX-CXVII."

Publicly, Pound spoke little about his work, but on the rare occasion he did, he described "The Cantos" as a failed work of poetry. Whether Pound truly felt that way about his defining work is often debated.

Death

Pound passed away in Venice in 1972 and was buried on the cemetery island Isole di San Michele. Over the course of his long, productive lifetime, Pound published 70 books of his own writing, had a hand in some 70 others and authored more than 1,500 articles.

Selected Poems by EZRA POUND

In A Station Of The Metro

by EZRA POUND

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

petals on a wet, black bough.L'Art

by EZRA POUND

Green arsenic smeared on an egg-white cloth,

Crushed strawberries! Come, let us feast our eyes.The Tree

by EZRA POUND

I stood still and was a tree amid the wood,

Knowing the truth of things unseen before;

Of Daphne and the laurel bow

And that god-feasting couple old

that grew elm-oak amid the wold.

'Twas not until the gods had been

Kindly entreated, and been brought within

Unto the hearth of their heart's home

That they might do this wonder thing;

Nathless I have been a tree amid the wood

And many a new thing understood

That was rank folly to my head before.The Garden

by EZRA POUND

En robe de parade. Samain

Like a skein of loose silk blown against a wall

She walks by the railing of a path in Kensington Gardens,

And she is dying piece-meal

Tof a sort of emotional anaemia.

And round about there is a rabble

Of the filthy, sturdy, unkillable infants of the very poor.

They shall inherit the earth.

In her is the end of breeding.

Her boredom is exquisite and excessive.

She would like some one to speak to her,

And is almost afraid that I

Twill commit that indiscretion.Salutation

by EZRA POUND

O generation of the thoroughly smug

and thoroughly uncomfortable,

I have seen fishermen picnicking in the sun,

I have seen them with untidy families,

I have seen their smiles full of teeth

and heard ungainly laughter.

And I am happier than you are,

And they were happier than I am;

And the fish swim in the lake

and do not even own clothing.The Return

by EZRA POUND

See, they return; ah, see the tentative

Movements, and the slow feet,

The trouble in the pace and the uncertain

Wavering!

See, they return, one by one,

With fear, as half-awakened;

As if the snow should hesitate

And murmur in the wind,

and half turn back;

These were the "Wing'd-with-Awe,"

Inviolable.

Gods of the Wingèd shoe!

With them the silver hounds,

sniffing the trace of air!

Haie! Haie!

These were the swift to harry;

These the keen-scented;

These were the souls of blood.

Slow on the leash,

pallid the leash-men!The Lake Isle

by EZRA POUND

O God, O Venus, O Mercury, patron of thieves,

Give me in due time, I beseech you, a little tobacco-shop,

With the little bright boxes

piled up neatly upon the shelves

And the loose fragment cavendish

and the shag,

And the bright Virginia

loose under the bright glass cases,

And a pair of scales

not too greasy,

And the votailles dropping in for a word or two in passing,

For a flip word, and to tidy their hair a bit.

O God, O Venus, O Mercury, patron of thieves,

Lend me a little tobacco-shop,

or install me in any profession

Save this damn'd profession of writing,

where one needs one's brains all the time.The River-Merchant's Wife: A Letter

by EZRA POUND

After Li Po

While my hair was still cut straight

across my forehead

I played at the front gate, pulling

flowers.

You came by on bamboo stilts, playing

horse,

You walked about my seat, playing with

blue plums.

And we went on living in the village of

Chokan:

Two small people, without dislike or

suspicion.

At fourteen I married My Lord you.

I never laughed, being bashful.

Lowering my head, I looked at the wall.

Called to, a thousand times, I never

looked back.

At fifteen I stopped scowling,

I desired my dust to be mingled with

yours

Forever and forever and forever.

Why should I climb the lookout?

At sixteen you departed,

You went into far Ku-to-en, by the river

of swirling eddies,

And you have been gone five months.

The monkeys make sorrowful noise

overhead.

You dragged your feet when you went

out,

By the gate now, the moss is grown,

the different mosses,

Too deep to clear them away!

The leaves fall early this autumn, in

wind.

The paired butterflies are already

yellow with August

Over the grass in the West garden;

They hurt me. I grow older.

If you are coming down through the

narrows of the river Kiang,

Please let me know beforehand,

And I will come out to meet you

As far as Cho-fu-sa.

(Translated by Ezra Pound)Canto XXXVI

by EZRA POUND

A Lady asks me

I speak in season

She seeks reason for an affect, wild often

That is so proud he hath Love for a name

Who denys it can hear the truth now

Wherefore I speak to the present knowers

Having no hope that low-hearted

Can bring sight to such reason

Be there not natural demonstration

I have no will to try proof-bringing

Or say where it hath birth

What is its virtu and power

Its being and every moving

Or delight whereby ‘tis called "to love"

Or if man can show it to sight.

Where memory liveth,

it takes its state

Formed like a diafan from light on shade

Which shadow cometh of Mars and remaineth

Created, having a name sensate,

Custom of the soul,

will from the heart;

Cometh from a seen form which being understood

Taketh locus and remaining in the intellect possible

Wherein hath he neither weight nor still-standing,

Descendeth not by quality but shineth out

Himself his own effect unendingly

Not in delight but in the being aware

Nor can he leave his true likeness otherwhere.

He is not vertu but cometh of that perfection

Which is so postulate not by the reason

But ‘tis felt, I say.

Beyond salvation, holdeth his judging force

Deeming intention to be reason's peer and mate,

Poor in discernment, being thus weakness' friend

Often his power cometh on death in the end,

Be it withstayed

and so swinging counterweight.

Not that it were natural opposite, but only

Wry'd a bit from the perfect,

Let no man say love cometh from chance

Or hath not established lordship

Holding his power even though

Memory hath him no more.

Cometh he to be

when the will

From overplus

Twisteth out of natural measure,

Never adorned with rest Moveth he changing colour

Either to laugh or weep

Contorting the face with fear

resteth but a little

Yet shall ye see of him That he is most often

With folk who deserve him

And his strange quality sets sighs to move

Willing man look into that forméd trace in his mind

And with such uneasiness as rouseth the flame.

Unskilled can not form his image,

He himself moveth not, drawing all to his stillness,

Neither turneth about to seek his delight

Nor yet to see out proving

Be it so great or so small.

He draweth likeness and hue from like nature

So making pleasure more certain in seeming

Nor can stand hid in such nearness,

Beautys be darts tho' not savage

Skilled from such fear a man follows

Deserving spirit, that pierceth.

Nor is he known from his face

But taken in the white light that is allness

Toucheth his aim

Who heareth, seeth not form

But is led by its emanation

Being divided, set out from colour,

Disjunct in mid darkness

Grazeth the light, one moving by other,

Being divided, divided from all falsity

Worthy of trust

From him alone mercy proceedeth.

Go, song, surely thou mayest

Whither it please thee

For so art thou ornate that thy reasons

Shall be praised from thy understanders,

With others hast thou no will to make company.

"Called thrones, balascio or topaze"

Eriugina was not understood in his time

"which explains, perhaps, the delay in condemning him"

And they went looking for Manicheans

And found, so far as I can make out, no Manicheans

So they dug for, and damned Scotus Eriugina

"Authority comes from right reason,

never the other way on"

Hence the delay in condemning him

Aquinas head down in a vacuum,

Aristotle which way in a vacuum?

Sacrum, sacrum, inluminatio coitu.

Lo Sordels si fo di Mantovana

of a castle named Goito.

"Five castles!

"Five castles!"

(king giv' him five castles)

"And what the hell do I know about dye-works?!"

His Holiness has written a letter:

"CHARLES the Mangy of Anjou….

..way you treat your men is a scandal…."

Dilectis miles familiaris…castra Montis Odorisii

Montis Sancti Silvestri pallete et pile…

In partibus Thetis….vineland

land tilled

the land incult

pratis nemoribus pascuis

with legal jurisdiction

his heirs of both sexes,

…sold the damn lot six weeks later,

Sordellus de Godio.

Quan ben m'albir e mon ric pensamen.Canto XVI

by EZRA POUND

And before hell mouth; dry plain

and two mountains;

On the one mountain, a running form,

and another

In the turn of the hill; in hard steel

The road like a slow screw's thread,

The angle almost imperceptible,

so that the circuit seemed hardly to rise;

And the running form, naked, Blake,

Shouting, whirling his arms, the swift limbs,

Howling against the evil,

his eyes rolling,

Whirling like flaming cart-wheels,

and his head held backward to gaze on the evil

As he ran from it,

to be hid by the steel mountain,

And when he showed again from the north side;

his eyes blazing toward hell mouth,

His neck forward,

and like him Peire Cardinal.

And in the west mountain, Il Fiorentino,

Seeing hell in his mirror,

and lo Sordels

Looking on it in his shield;

And Augustine, gazing toward the invisible.

And past them, the criminal

lying in the blue lakes of acid,

The road between the two hills, upward

slowly,

The flames patterned in lacquer, crimen est actio,

The limbo of chopped ice and saw-dust,

And I bathed myself with acid to free myself

of the hell ticks,

Scales, fallen louse eggs.

Palux Laerna,

the lake of bodies, aqua morta,

of limbs fluid, and mingled, like fish heaped in a bin,

and here an arm upward, clutching a fragment of marble,

And the embryos, in flux,

new inflow, submerging,

Here an arm upward, trout, submerged by the eels;

and from the bank, the stiff herbage

the dry nobbled path, saw many known, and unknown,

for an instant;

submerging,

The face gone, generation.

Then light, air, under saplings,

the blue banded lake under æther,

an oasis, the stones, the calm field,

the grass quiet,

and passing the tree of the bough

The grey stone posts,

and the stair of gray stone,

the passage clean-squared in granite:

descending,

and I through this, and into the earth,

patet terra,

entered the quiet air

the new sky,

the light as after a sun-set,

and by their fountains, the heroes,

Sigismundo, and Malatesta Novello,

and founders, gazing at the mounts of their cities.

The plain, distance, and in fount-pools

the nymphs of that water

rising, spreading their garlands,

weaving their water reeds with the boughs,

In the quiet,

and now one man rose from his fountain

and went off into the plain.

Prone in that grass, in sleep;

et j'entendis des voix:…

wall . . . Strasbourg

Galliffet led that triple charge. . . Prussians

and he said [Plarr's narration]

it was for the honour of the army.

And they called him a swashbuckler.

I didn't know what it was

But I thought: This is pretty bloody damn fine.

And my old nurse, he was a man nurse, and

He killed a Prussian and he lay in the street

there in front of our house for three days

And he stank. . . . . . .

Brother Percy,

And our Brother Percy…

old Admiral

He was a middy in those days,

And they came into Ragusa

. . . . . . place those men went for the Silk War. . . . .

And they saw a procession coming down through

A cut in the hills, carrying something

The six chaps in front carrying a long thing

on their shoulders,

And they thought it was a funeral,

but the thing was wrapped up in scarlet,

And he put off in the cutter,

he was a middy in those days,

To see what the natives were doing,

And they got up to the six fellows in livery,

And they looked at it, and I can still hear the old admiral,

"Was it? it was

Lord Byron

Dead drunk, with the face of an A y n. . . . . . . .

He pulled it out long, like that:

the face of an a y n . . . . . . . . gel."

And because that son of a bitch,

Franz Josef of Austria. . . . . .

And because that son of a bitch Napoléon Barbiche…

They put Aldington on Hill 70, in a trench

dug through corpses

With a lot of kids of sixteen,

Howling and crying for their mamas,

And he sent a chit back to his major:

I can hold out for ten minutes

With my sergeant and a machine-gun.

And they rebuked him for levity.

And Henri Gaudier went to it,

and they killed him,

And killed a good deal of sculpture,

And ole T.E.H. he went to it,

With a lot of books from the library,

London Library, and a shell buried ‘em in a dug-out,

And the Library expressed its annoyance.

And a bullet hit him on the elbow

…gone through the fellow in front of him,

And he read Kant in the Hospital, in Wimbledon,

in the original,

And the hospital staff didn't like it.

And Wyndham Lewis went to it,

With a heavy bit of artillery,

and the airmen came by with a mitrailleuse,

And cleaned out most of his company,

and a shell lit on his tin hut,

While he was out in the privy,

and he was all there was left of that outfit.

Windeler went to it,

and he was out in the Ægæan,

And down in the hold of his ship

pumping gas into a sausage,

And the boatswain looked over the rail,

down into amidships, and he said:

Gees! look a' the Kept'n,

The Kept'n's a-gettin' ‘er up.

And Ole Captain Baker went to it,

with his legs full of rheumatics,

So much so he couldn't run,

so he was six months in hospital,

Observing the mentality of the patients.

And Fletcher was 19 when he went to it,

And his major went mad in the control pit,

about midnight, and started throwing the ‘phone about

And he had to keep him quiet

till abut six in the morning,

And direct that bunch of artillery.

And Ernie Hemingway went to it,

too much in a hurry,

And they buried him for four days.

Et ma foi, vous savez,

tous les nerveux. Non,

Y a une limite; les bêtes, les bêtes ne sont

Pas faites pour ça, c'est peu de chose un cheval.

Les hommes de 34 ans à quatre pattes

qui criaient "maman." Mais les costauds,

La fin, là à Verdun, n'y avait que ces gros bonshommes

Et y voyaient extrêmement clair.

Qu'est-ce que ça vaut, les généraux, le lieutenant,

on les pèse à un centigramme,

n'y a rien que du bois,

Notr' capitaine, tout, tout ce qu'il y a de plus renfermé

de vieux polytechnicien, mais solide,

La tête solide. Là, vous savez,

Tout, tout fonctionne, et les voleurs, tous les vices,

Mais les rapaces,

y avait trois dans notre compagnie, tous tués.

Y sortaient fouiller un cadavre, pour rien,

y n'serainet sortis pour rien que ça.

Et les boches, tout ce que vous voulez,

militarisme, et cætera, et cætera.

Tout ça, mais, MAIS,

l'français, i s'bat quand y a mangé.

Mais ces pauvres types

A la fin y s'attaquaient pour manger,

Sans orders, les bêtes sauvages, on y fait

Prisonniers; ceux qui parlaient français disaient:

"Poo quah? Ma foi on attaquait pour manger."

C'est le corr-ggras, le corps gras,

leurs trains marchaient trois kilomètres à l'heure,

Et ça criait, ça grincait, on l'entendait à cinq kilomètres.

(Ça qui finit la guerre.)

Liste officielle des morts 5,000,000.

I vous dit, bè, voui, tout sentait le pétrole.

Mais, Non! je l'ai engueulé.

Je lui ai dit: T'es un con! T'a raté la guerre.

O voui! tous les homes de goût, y conviens,

Tout ça en arrière.

Mais un mec comme toi!

C't homme, un type comme ça!

Ce qu'il aurait pu encaisser!

Il était dans une fabrique.

What, burying squad, terrassiers, avec leur tête

en arrière, qui regardaient comme ça,

On risquait la vie pour un coup de pelle,

Faut que ça soit bein carré, exact…

Dey vus a bolcheviki dere, und dey dease him:

Looka vat youah Trotzsk is done, e iss

madeh deh zhamefull beace!!

"He iss madeh de zhamefull beace, iss he?

"He is madeh de zhamevull beace?

"A Brest-Litovsk, yess? Aint yuh herd?

"He vinneh de vore.

"De droobs iss released vrom de eastern vront, yess?

"Un venn dey getts to deh vestern vront, iss it

"How many getts dere?

"And dose doat getts dere iss so full off revolutions

"Venn deh vrench is come dhru, yess,

"Dey say, "Vot?" Un de posch say:

"Aint yeh heard? Say, ve got a rheffolution."

That's the trick with a crowd,

Get ‘em into the street and get ‘em moving.

And all the time, there were people going

Down there, over the river.

There was a man there talking,

To a thousand, just a short speech, and

Then move ‘em on. And he said:

Yes, these people, they are all right, they

Can do everything, everything except act;

And go an' hear ‘em but when they are through

Come to the bolsheviki…

And when it broke, there was the crowd there,

And the cossacks, just as always before,

But one thing, the cossacks said:

"Pojalouista."

And that got round in the crowd,

And then a lieutenant of infantry

Ordered ‘em to fire into the crowd,

in the square at the end of the Nevsky,

In front of the Moscow station,

And they wouldn't,

And he pulled his sword on a student for laughing,

And killed him,

And a cossack rode out of his squad

On the other side of the square

And cut down the lieutenant of infantry

And there was the revolution…

as soon as they named it.

And you can't make ‘em,

Nobody knew it was coming. They were all ready, the old gang,

Guns on the top of the post-office and the palace,

But none of the leaders knew it was coming.

And there were some killed at the barracks,

But that was between the troops.

So we used to hear it at the opera

That they wouldn't be under Haig;

and that the advance was beginning;

That it was going to begin in a week.